As consumers continue to stay at home and apart amid the pandemic, there is one thing that continues to connect us all: that eager anticipation of the arrival of the bubble-wrapped happiness we purchased just a few days before.

More than the joy that consumers get from online retail therapy, the industry that makes the delivery of these small packages happen, aka logistics, can potentially contribute to the Southeast Asian economy over $108 million a year, and a whole host of benefits, says the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), if certain policies and regulations are improved across the region to allow for a more competitive business environment for such companies.

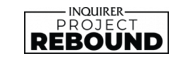

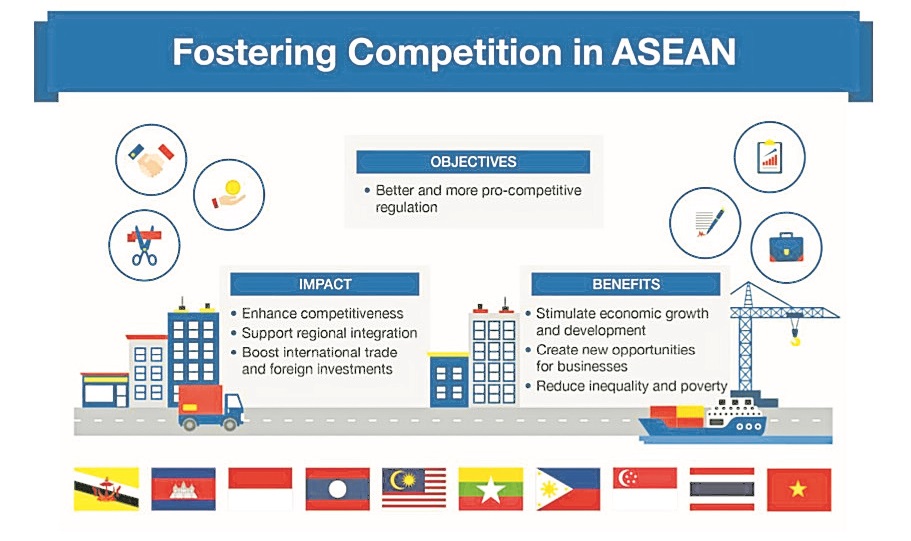

As a global organization of representatives from governments, parliaments, international organizations, business and labor and civil society that work together to “build better policies for better lives,” the OECD specifies these benefits in its recent reports “OECD Competitive Neutrality Reviews: Small-Package Delivery Services in Asean” and “OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Logistics Sector in Asean.”

These include increases in:

- Consumer welfare (e.g. through lower prices)

- Foreign direct investment (FDI) into the small-package delivery services sector

- Development of SMEs (small and medium enterprises) and employment

- Cross-border trade and gender equality

Lowering small-package shipping rates, for instance, could potentially infuse the Asean economy with over $108 million a year for each 1 percent decrease in delivery prices, says the OECD in its Neutrality Reviews report. By 2025, it’s a benefit that could increase to almost $165 million, given that the market for small-package delivery services is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 12 percent between 2020 and 2025.

“As we seek to optimize the strength and the quality of the recovery, greater openness and procompetitive reforms will be a crucial element to stimulate the growth of new businesses and jobs, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, which account for almost 90 percent of all enterprises across the whole bloc and nearly half of all employment,” says Mathias Cormann, secretary general of the OECD.

According to the OECD reports, rethinking regulations governing FDI in the logistics sector would help member states grow their economies, and that it has been estimated that reducing barriers to trade and FDI restrictions could deliver a boost to GDP (gross domestic product) of up to 17 percent over the medium to long-term.

Additionally, the Neutrality Reviews report cites the gender dimension of pro-competitive policies, highlighting that “some studies estimate that the removal of gender bias in the economy, including logistics, may increase GDP in the region by up to 30 percent.”

Achieving these benefits entails a reassessment of regulation on competition in the logistics sector, states the OECD, across five main subsectors of the market: freight transportation, including transport by road, inland waterway, and maritime; freight forwarding; warehousing; small-package delivery services; and value-added services. In the Assessment Reviews report, OECD lists these key sector recommendations:

- Remove restrictive provisions setting quotas on the number of permits for cross-border road freight transport and replace with a license system. Licensing criteria should be clearly defined in the international agreement or implementing laws or regulations. Alternatively, assess market need and demand every one to three years, and consider increasing the number of licenses that can be issued.

- Avoid limitations on the number of authorized road freight transport carriers. Market-access requirements—such as professional competency or technical conditions for vehicles—should be clearly laid down in the law.

- Review regulations or provisions that limit the areas in which road freight transport licensees can operate, so that they can provide their services without any geographic restrictions. Furthermore, review regulations or provisions that limit firms’ fleet size, by restricting new-vehicle registrations or imposing a minimum or maximum number of vehicles, while maintaining provisions that pursue a legitimate policy objective (such as safety or environmental protection).

- Ensure that regulations imposing safety requirements and roadworthiness inspections on road freight transport licensees are clear and proportionate to the pursued policy goal and do not generate excessive costs.

- Open the domestic shipping market to Asean competition by lifting the ban on Asean vessels carrying domestic cargo.

- Remove excessive licensing requirements for domestic shipping, such as vessel ownership, economic-needs tests and the submission of business plans.

- When selecting port or terminal operators and port service providers, use open tender processes rather than direct negotiation. Adopt best practices for tender processes and concessions.

- Ensure clear separation between the regulatory and operational functions of port authorities to avoid real or perceived conflicts of interest.

- Only allow the regulation of maximum prices, not minimum prices, in cases where competition is limited. Maximum prices should be regularly revised to ensure they are in line with market dynamics and provide the necessary incentives for innovation and investment.

- Implement planned railway sector reform and initiate regulatory reforms that can foster competition in freight transport services by railway. This could involve some form of separation between infrastructure management and rail freight transport service operations.

- Legislate the requirement to grant third-party access to railway infrastructure to ensure access for new entrants on transparent and non-discriminatory terms. In order to make this requirement effective, ensure that the regulator or the relevant ministerial department has broad powers to intervene in the market, for example, allow it to set and enforce access charges and conditions.

The Neutrality Reviews report also examined the effects of state-owned enterprises on competition in the bloc’s small-package delivery market. This market segment is a critical part of the logistics industry due to its role in the rapid expansion of e-commerce, whose growth has been dramatically accelerated by COVID-19, says the OECD.

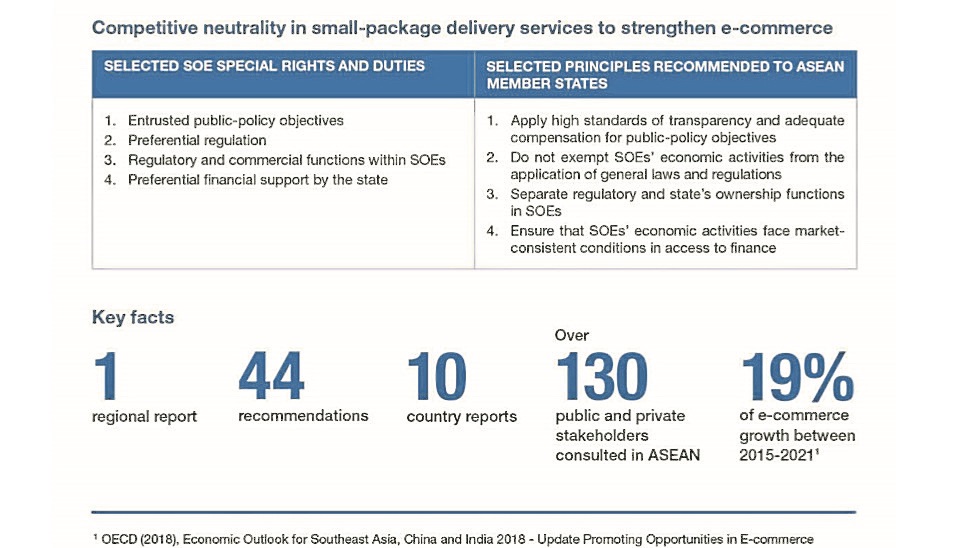

The two reports are part of the OECD’s “Fostering Competition in Asean” project, a partnership between the OECD and Asean, supported by the UK Government’s Asean Economic Reform Program. It reviews regulatory constraints on competition in all 10 Asean member-states to identify regulations that hinder the efficient functioning of markets and may unlevel the playing field to the disadvantage of businesses and consumers.

Read more at https://www.oecd.org/competition/fostering-competition-in-asean.htm.